The early 1990s were dominated by artists who examined the political and critical potentials of art, with a particular interest in its site-specificity. Not unlike the hardliners among the conceptual artists of the 1960s, the representatives of this younger generation emphasized not the creation of an artistic product but rather the visualization of an idea. That was the climate when Stefan Müller began to study painting under Thomas Bayrle at the Stadelschule in Frankfurt in 1996. At the time, his creative out-put was shaped by his doubts whether it was even still possible to paint a picture at the end of the 20th century. Nonetheless, the engagement with the medium of painting and the question of what its formal significance may yet be for the present, after Conceptual Art and Minimal Art, were always central to his approach to his art.

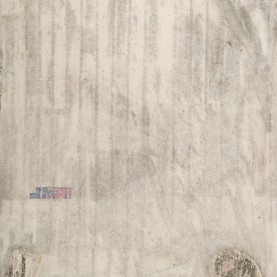

Even in his early works, Müller experimented with a variety of pictorial surfaces and materials. Employing a minimalist approach, he explores the picture, often considering it finished at an early point in time. Minimal traces that seem to have been created by accident while stretching the canvas are often enough to form a complete picture. With this attitude, Müller takes up central questions of post-conceptual visual production.

Müller’s painting is distinguished by a reduced choice of materials, motifs, and colors. He paints on untreated canvas, cotton fabric, or used fabrics such as bed sheets, which he exposes to accidental modification before and during the act of painting. Beerstains, ashes, dust, coffee, or blood often replace the conventional varnish. His palette of materials ranges from acrylic, transparent lacquers, oil, and silicone to markers, pencils, and crayons. He also integrates banal elements such as dirt, tissue paper, confetti, and glitter into his works.

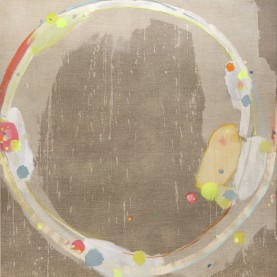

In the pictures from the early 2000s, Stefan Müller is still palpably torn by the conflict between representational and abstract painting. Giraffes rambling across the canvas or a drum kit dissolve into abstract patterns of color. Yet Müller soon develops the formal vocabulary of circles, spheres, lines, and rectangular fields that pervades his work to this day. Curls become the I, circles represent the thoughts incessantly spinning in the artist’s head.

The protagonists of Minimal Art confidently resisted the traditional expressive means of painting and sculpture. Trademarks of their three-dimensional works include an extremely reduced formal language, modern industrial materials such as plywood, aluminum, and fluorescent tubes, and the removal of anything suggesting the artist’s individual hand. The products of American Color Field Painting are defined exclusively by visual illusionism, negating the traditional representational function of painting. Palermo’s fabric paintings likewise categorically eliminate the personal artistic signature. His pictures made of dyed panels of fabric, having lost all painted materiality, are radically reduced to the impression of color.

If Müller begins in the mid-2000s to develop a form of painting without painting by transforming fabrics of various composition, size, and color into works of art in a purely additive process, this must certainly be considered a reference to Minimal Art. “And indeed, time and again, his works give us certain glimpses of allusions to traditions in painting such as Hard Edge and Color Field Painting… Yet such allusions are in Müller’s work fairly scattered and always refracted; their realization is usually pretty rude, radically simplified, or so banal that the presumable source seems to come back to us as nothing more than an echo of our own hunch. References are framed in sufficiently vague ways and almost dissolve into Müller’s own visual world: as something that resonates without dominating. A recollection that may well turn into something else entirely.” Mistakes and ruptures often mark Müller’s fabric paintings, implying the Romantic notion of failure.